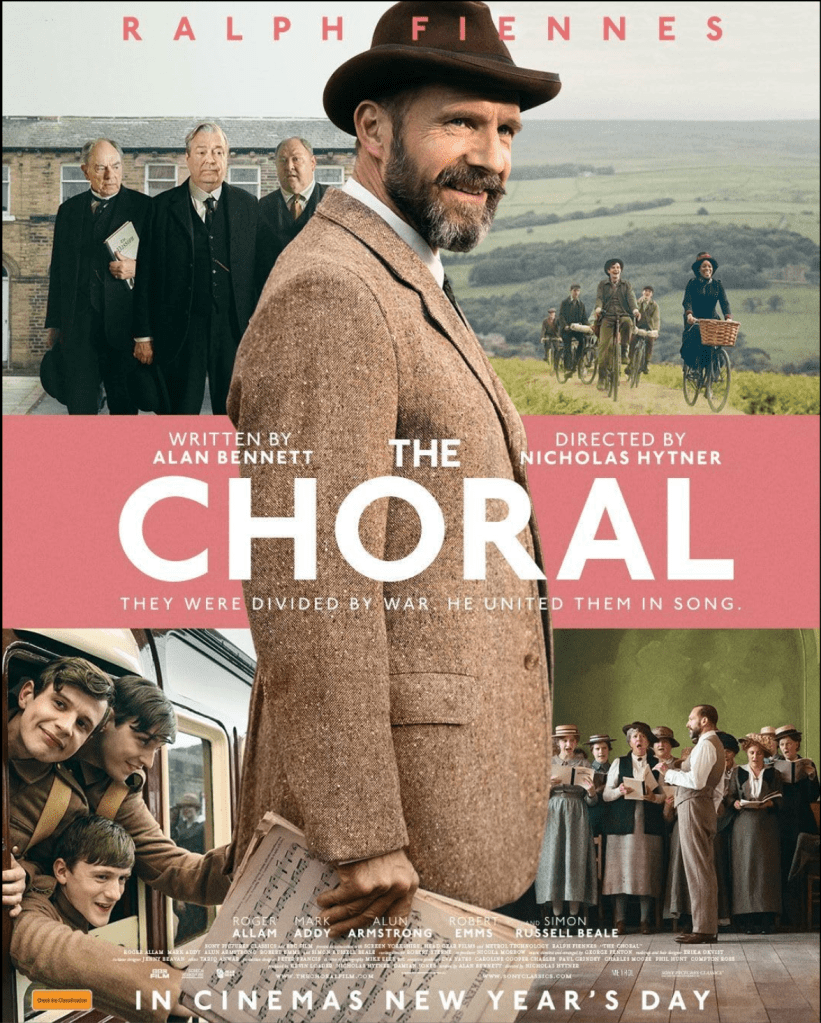

The new film The Choral, starring Ralph Fiennes, is a historical drama set in 1916, in a small mill town in England, during World War I. Most of the town’s young men have either signed up or been called up for service, and that absence has left the local choral society without its male voices. At the time, the choral society was an important part of community life.

With so many men gone, the leaders of the society set out to find new voices, younger men who have not yet gone off to war, to keep the choir alive for its annual production. On the surface, it’s a very simple story that carries a lot of emotional weight without ever needing to raise its voice.

Story Summary

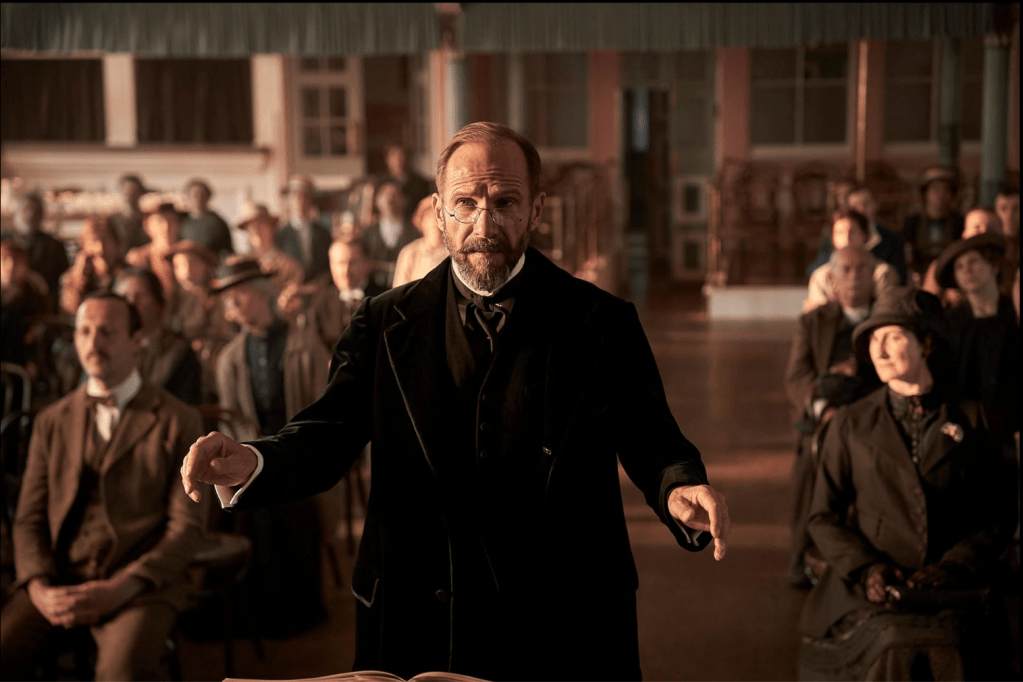

The Choral centers on a new music director brought in to save the struggling choral in a small English town. Ralph Fiennes plays the replacement director, Dr Henry Guthrie, and he is simultaneously the best possible choice and the worst. He has extraordinary talent and training, having studied music and conducting in Germany, where he also built his career before returning home as war broke out. He knows exactly what he is doing. He demands excellence. He expects precision. He pushes the singers to be better than they ever thought they could be and challenges them to find others who could add their voices to the town’s choral society.

That same German connection that made Guthrie such an excellent choice is also a serious obstacle since anything associated with Germany is suspect. Even more challenging, nearly all of the choral works available to the society have German ties, including their original plan to perform Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. Not a great position for a new choral director or a choral looking to give a performance in England. They find themselves suddenly trapped between musical integrity and political reality.

To work around this, they make a risky decision. They choose to perform The Dream of Gerontius, by English composer Sir Edward Elgar, which is a notoriously difficult piece that was previously performed with disastrous results. Despite the odds, they decide to attempt it again, and this decision becomes the turning point of the film where everything starts to come together … until it doesn’t.

From there, the story expands outward as they search for new voices to fill the missing bass lines, even as military conscription looms over every young man in town. The choral members turn to recruiting men from all walks of life, ranging from the telegram messengers to a man who sings casually at the local pub (with a beer in his hand, of course), soldiers recovering in a hospital, and a recently returned serviceman who finds that the life he left behind no longer exists. These are people would never have been considered before, and many of them would never have imagined joining the choral, but suddenly they had something new and hopeful in their lives. When you’re about to go off to war, or just coming back, that is such an important thing to hold onto.

First Impressions

One of the strongest aspects of this film is its writing. You can really see what a good writer can accomplish with a script that trusts the audience. The opening scene sets the tone beautifully. Young men preparing to go to war visit a local photographer offering free or heavily discounted portraits. These photos are meant as keepsakes for families, because no one knows if these men will return. That single choice establishes the stakes immediately.

The film then introduces two young men who bicycle together delivering mail, including official telegrams with news from the Front. Many of the letters they carry are brown envelopes, and everyone knows what those mean. These deliveries become a recurring visual and emotional motif throughout the film. Some moments are never spoken aloud, yet the meaning is unmistakable. A letter handed over to a woman with a child holding onto her skirts. An awkward pause. A look of undisguised pain followed by the weight of loss that settles in as the scene and the world moves on, leaving a devastated family behind.

Through these moments, the film also hints at the music director’s friendship with a young soldier serving abroad and with a conscientious objector at home, and the nature of those relationships is left deliberately ambiguous for a while. It could be friendship. It could be something more. It could be simply a complicated friendship. What matters is that it adds emotional complexity and gives us another perspective on the war that we rarely see and the kinds of friendships that are simply not talked about.

Music, Loss, and Identity

The rehearsals themselves are filled with quiet revelations. Longtime choir members suddenly see themselves through the eyes of a new director and realize that their skill may not be what they believed it was and recognizing their own failures when doing something the love is a hard thing to bear. For people who have devoted years of their lives to this choral, that realization is painful. Music is not just a hobby for them. It’s about the singers’ identities at this point in time, and because Gerontius is about death and the redemption of a young man’s soul, it’s also a way for the townspeople to confront death without actually naming what they’re doing. It is belonging and it’s the thing that gets them from one moment to the next.

The film handles this with real sensitivity. It asks what happens when something that once gave you purpose is no longer enough, and how people adapt when the world changes around them and when the people you love just never return.

This theme extends beyond the choral. The war creates a constant tension between everyday life and unimaginable loss. People still go to work. They still earn money. They still try to build families and get through their days. At the same time, young men are disappearing, sometimes forever and sometimes in almost unrecognizable condition. There is a widening gap between those living at home and those fighting abroad, and until the war touches you directly, it remains abstract. That feeling is tangible here, and the film captures that disconnect beautifully. When young men leave for service, they go with idealism and a belief that they are contributing to something important. They believe they will return, every one of them. The audience, however, understands the cost and the truth about what boarding that train out of town actually means. That awareness adds a layer of sadness to every farewell that isn’t really touched on directly, but is felt in the small pauses and silences during and after the goodbyes are made.

Performance and Ensemble Strength

Ralph Fiennes is extraordinary in this role as Guthrie. I recently watched him in 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, and the contrast between that character and this one is astonishing. Here, he plays a sensitive, deeply musical man who longs for the Germany he loved, a Germany of art, culture, and music that no longer exists.

He is an outcast in his own country, viewed with suspicion because of his past choices, yet completely devoted to his work. Fiennes disappears into this role. You stop seeing the actor and only see the character. That level of transformation is rare, and it speaks to an uncommon level of excellence.

This is very much an ensemble film, and the supporting cast is excellent. Their hopes, fears, frustrations, and quiet resilience feel authentic. Even when the story does not revolve directly around the music director, everything connects back to him. He becomes the emotional and structural center that allows the entire cast to work as a cohesive whole.

Historical Detail and Emotional Crescendo

The film captures this historical moment, highlighting the cultural force of working-class choral traditions and the growing sense of musical nationalism in works from composers like Edward Elgar. From the set design to the dialog, the social expectations, and the emotional landscape – all of these things feel authentic and believable. Some elements are lightly idealized to heighten contrast, but it never feels dishonest.

One of the most powerful scenes comes near the end. The man who funds the choral, Alderman Duxbury, the town’s mill owner and chairman of the Choral Society, has lost his son in the war and his wife has retreated into a near permanent state of mourning. Supporting the choral has become a way for him to survive that loss. And, there is this ending monologue in which he quietly describes how the platform felt when his son left for war, and the train platform was filled with celebration and music. There was a band to play them off as loved ones stayed behind waving as the train disappeared into the distance and the music faded. Then with each newly departing train, over time, the platform grew quieter with fewer people to cheerfully bid their men farewell. Eventually, there was no music at all and that is why he funded the choral.

That moment perfectly captures the film’s core idea. Music is the thread that connects life at home to those who leave. When the music disappears, the loss becomes undeniable in the silence.

Recommendation

Is The Choral worth the price of a ticket? For the right audience, absolutely. The Choral is a human-centered story about the people who are left behind during wartime. It reveals the layered experiences of life on the home front during early modern warfare, when daily routines continue even as loss and uncertainty quietly reshape a community trying to put up a brave and hopeful face. This is a film about how communities adapt and traditions endure through the preservation of art and music, which become a lifeline between the characters’ present and their future. The story’s themes are universal, portrayed in simple and honest ways that feel relatable if you are able to stop and listen.

As I think back on the film as I write this review, I can’t help wondering how well a younger audience will connect with the historical nature of the story because the distance between World War I and 2026 is so wide. I really hope that younger viewers will actively seek out this film since it gives an important and increasingly rare view into a period of time that is fading from memory and is at risk of being forgotten.

Viewers who appreciate human-centered stories about wartime life will find a lot to connect with in The Choral. The writing is strong, and while the film tells a different side of World War I’s story, it feels part of a larger conversation about war, morality, and the people caught in the margin. If you enjoyed films like The History of Sound, The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, Nuremberg or other historical dramas, I think this film is likely to resonate with you as well.

If historical films, small town war stories, or music-driven narratives are not your thing, this may not be your kind of movie. It’s a bit naive at times compared to today, but that’s part of its charm. This is a thoughtful, emotionally resonant film that takes its time, and it asks the audience to sit with its quiet moments in this small English town rather than focusing on the spectacle of the war itself.

If you are a fan of Ralph Fiennes, this performance alone makes the film worth watching. The Choral is quietly powerful, and it stays with you long after it ends.

Have you seen it? Are you planning to? Do you enjoy World War I or World War II films that focus on life at home rather than the battlefield? I would love to hear your thoughts and any recommendations for other films that explore this side of wartime experience.

If you enjoyed this review, please give it a like and subscribe for more. You can also visit my YouTube channel at @ErinUnderwoodfor more videos.